Explore the connection between Bauhaus ideals and the Brutalist vision through the journey of László Tóth in The Brutalist

Introduction

László Tóth was a student at the Bauhaus school on the Dessau campus. The character in the film is based on various contributors to the Bauhaus and Brutalism movements, and in my opinion, he most closely resembles Marcel Breuer. However, the true intention of director Brady Corbet was to present a fictional character who did not represent any single person but rather this small generation of artists who lived through these social, political, and wartime conflicts that in some way inspired their work as artists and craftsmen.

If this introduction is still unclear, I recommend watching The Brutalist (2024) to fully understand this analysis. This discussion will not focus on the film’s plot but rather on the social, political, artistic, historical, and anthropological themes surrounding its more than three-hour runtime.

Bauhaus

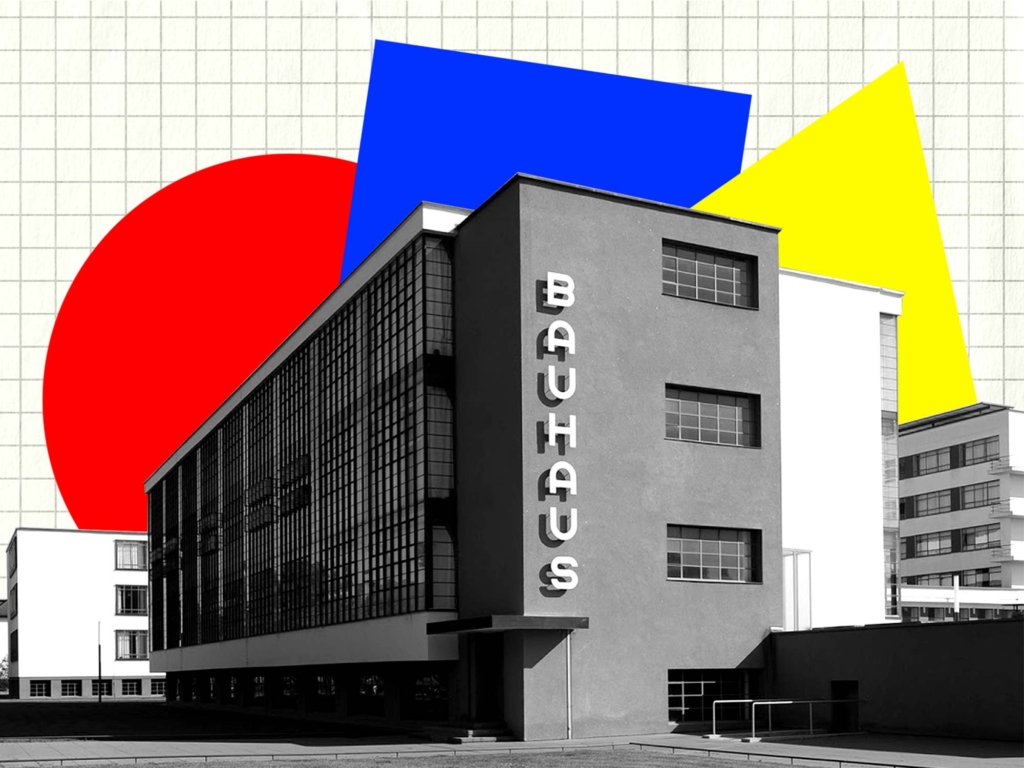

To begin understanding our main character, László Tóth, let’s examine his time at the Bauhaus school. Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius in a Germany filled with post-war uncertainty, political turmoil, and social changes, Gropius developed a manifesto outlining his vision of art and its potential. In summary, he advocated for the unification of both artistic and technical disciplines, emphasizing that design should be functional, serve society, and reflect the modern, industrial era, leaving behind the ostentation of the past in favor of simple, direct aesthetics.

The manifesto did not remain just theoretical; it genuinely attracted many influential figures to participate in this new concept. It brought together disciplines by inviting individuals such as Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Schlemmer, among others. Johannes Itten was responsible for creating the preparatory course (Vorkurs), which aimed to erase everything students thought they knew, breaking mental barriers and promoting a holistic understanding of the arts. This course focused on exploring materials and techniques in painting, textiles, sculpture, and more to understand their properties and potential. Topics such as color theory, personal expression, interdisciplinary approaches, and a culture of constructive criticism helped guide students toward Gropius’s vision.

The Bauhaus, originally established in Weimar, faced opposition and, after a 1923 exhibition received mixed reactions, moved to Dessau, where it built its iconic campus. With the rise of the Nazi regime, the school faced increasing pressure and was forced to close in 1933. After Gropius, the school was led by Hanns Meyer and Mies van der Rohe, lasting only fourteen years. Despite its short existence, its ideals lived on, inspiring movements like Brutalism, though the dream of changing the world through design was ultimately overshadowed by reality, in this case, World War II.

Brutalism

So far, I have focused solely on the Bauhaus because it was the precursor to Brutalism, providing essential context to understand both movements. They are connected through shared principles of functionality, the use of industrial materials, opposition to ornamentation, social commitment, and the influence of key figures in modern architecture.

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate

However, there are two key differences worth noting about Brutalism: First, the use of raw concrete (béton brut in French), from which the movement gets its name. Secondly, the historical context while Bauhaus was a response to World War I, Brutalism was a response to World War II. Despite these differences, the fundamental principles remained the same, adapted to different circumstances, and László Tóth serves as a figure connecting these movements.

Brutalism in the film:

“I think it’s the combination of minimalism and maximalism that I find really appealing. It’s not middle-brow. It’s very radical. For us, we’re thinking this is a very powerful visual allegory for how post-war psychology and post-war architecture are intrinsically linked.”

— Brady Corbet, The Brutalist Q&A with Brady Corbet | TIFF 2024

László Tóth

László Tóth, who resembles Marcel Breuer in both his Hungarian nationality and the famous Wassily Chair seen in the film, absorbed the Bauhaus ideology and culture. Like Gropius, he shared the dream of changing the world through design, but war not only took away his alma mater, it took away his entire life. Despite everything, László never forgot where he came from, his principles, or his identity. This strong sense of self, shapes his journey throughout his years in the United States.

Upon arriving, László thanks his cousin Attila for welcoming him. He has left everything behind in search of a better future in a country driven by progress, especially after the war. However, when Attila later expels him, this promised progress disappears. László lives in shelters, takes drugs, works for minimum wage, and gets into fights. The once-respected architect now finds himself in a world that seems to have no need for his talent and utopian vision.

The Americans had their own utopia, one deeply tied to capitalism, rather than the socialist ideals many European architects had embraced. This is reflected in Harrison Lee Van Buren, a wealthy magnate who views everything through a monetary lens. Harrison believes he can buy anything, even László.

“We get the sense that this is a man who, on some level, is ticking off boxes and thinking: ‘If I own this, if I’m successful at that, if I present myself this way, if I have these people around me, then I’m doing well in the world. Here is my identity. This is who I am.’”

— Guy Pearce, The Brutalist: Adrien Brody, Guy Pearce, and Felicity Jones on the construction of their characters

This sets up two opposing characters; László, who has a strong sense of identity, trying to rebuild his life, and Harrison, who is attempting to create a life but without a true identity, guided only by ego. Yet, their connection enables each to pursue their dreams: László to reclaim his place as an architect and Harrison to further build his status and legacy.

As the film progresses, their relationship becomes tense. Harrison, lacking an understanding of architecture and Brutalist principles, tries to take control of the project. Meanwhile, László becomes mentally and physically exhausted, sacrificing his time, family, and even financial stability to protect his artistic vision.

For László, this building is more than just a project, it embodies his ideology and his healing process after the trauma of war. However, rather than being therapeutic, it becomes an obsession, much like Harrison’s drive for more.

At a breaking point, László and his wife, Erzsébet, reflect on their lives. They realize that what they truly need is family, not America. After years of living as immigrants in a society that never fully accepted them, they decide to leave in search of a place where they are valued as people, not just for László’s talent. Much of the film revolves around this failed American dream.

Ending & Conclusion

Years later, after Erzsébet’s death, László is recognized at a biennale in Venice for his work in Pennsylvania. His niece Zsófia speaks on his behalf. Her words reveal the true meaning of his masterpiece. It was an obsession, but also a means of healing. It preserved memories, both traumatic and loving, particularly those tied to Erzsébet. Having survived a concentration camp, László had an intense desire to create, to do everything he had been forbidden to do for years. As an act of gratitude for his survival and in honor of those who didn’t make it.

He was able to leave behind a physical legacy. An artistic expression that provokes the viewer to remember where it comes from: it comes from an atrocious past due to wars, it speaks of the need for equality, it is a look towards a better future, where mental barriers are broken. László lived firm to his principles. After an arduous life filled with pain and struggle, he did help change the direction of the world through art and design. A dream of an entire generation that was many times shattered, finally came true.

— Zsófia “It is the destination, not the journey.”

Bibliography

BBC Arts. (2019). Bauhaus 100: A BBC Arts Documentary [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwYZQjgUljA

Corbet, B. (2025, February 25). Brady Corbet: The Brutalist interview. GQ. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/brady-corbet-the-brutalist-interview

Corbett, B. (2024). The Brutalist Q&A with Brady Corbet | TIFF 2024. [Video]. Toronto International Film Festival. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-o2IR8MoFQ

Brody, A., Pearce, G., & Jones, F. (2023). The Brutalist: Adrien Brody, Guy Pearce, and Felicity Jones on the construction of their characters [Video]. Letterboxd. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErTUFRabM9M